Israel and the Palestinians: Conflict, Coexistence, and Cooperation

This blog post is brought to you by Liad M…

May 17, 2016-The West Bank

Gush Etzion

“Our father’s footsteps went through here.” Embarking on a day in the Israeli occupied Palestinian territories began with an account of Judaism’s biblical connection to the Gush Etzion junction. The flourishing modernity of the area concealed its rich religious, and now political implications. More than 2,000 years ago, Gush Etzion was the center of the Path of Patriarchs, in which Abraham traveled from the holy city of Hebron to Jerusalem. Asserting her statements decisively through a proud demeanor, the Israeli soldier talking to us utilized historical biblical accounts to convey Jew’s right to the land. Though lost in biblical times, and throughout the 20th century, Jews have maintained ties to the agricultural communities that now flourish in the West Bank.

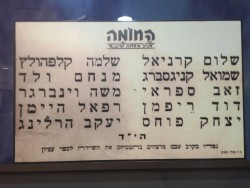

“Get the bread out of the rocks.” The rocky hills of the West Bank at first glance, desolate and arid, make one wonder how communities sustain themselves. One quick turn presents Kfar Etzion, a Jewish settlement with vibrant green shrubbery and thriving agriculture. “Not everything is easy in this country but lets try.” Kfar Etzion in the Gush Etzion junction did just that. They tried, and they tried again. Established in 1927, Yemenite Jews yearned for a settlement between the holy cities of Hebron and Jerusalem, tirelessly working to tend the arid land, yearning for transformation. Suffering numerous setbacks in conflicts with native Palestinians and Jordanians, the community was finally re-established after the 1967 war. The community maintains a vibrant aura, with a pleasant aroma and beautiful environment.

Efrat

“I don’t believe in fences.” The awe of the quality of Jewish communities in the West Bank continued with Efrat, a settlement of 10,000 residents. Speaking to the mayor of the community, which is 5 miles long and can be considered a city in relative terms, our group was provided with an alternative notion of Jewish building in the West Bank. My peers and I were in awe finding out that there is no security fence surrounding the community, supposedly developing strong relations with neighboring Palestinians. The mayor was articulate and eloquent, describing his firm belief in a peaceful coexistence based on mutual respect and economic cooperation, shedding light on the positive nature of Jewish construction east of Jerusalem.

“I’m willing to give up my house for true peace.” Hearing these words come from the mayor of a large settlement bloc on what is internationally recognized as Palestinian land is unwarranted. The mayor enlightened us that he has yearned for peace his whole life, noting the tragedy of Palestinian-Israeli relations. Alluding to previous peace process developments, he argued for Israel’s positive and progressive character, citing Egyptian and Jordanian peace plans. It was extremely enlightening for the group to hear his perspective on international law, teaching us that Israel took control of the territories after Jordan denounced them in 1967. His historical context made us question the justification for a Palestinian state, based on prior negotiations and international law, views not previously talked about by other speakers.

Beit Sahour

“They control everything. We don’t control anything.” Meeting with the Palestinian Mayor of the Beit Sahour Municipality conveyed a different reality, evoking sympathy and frustration within our group. The journey from Efrat to Beit Sahour was one of thriving agriculture and public life to a place where the mayor was boasting about the first indoor basketball gym in the area. Embodying the Palestinian narrative, the mayor spoke of justice, nationalism, and the Palestinian right to historic Palestine. However, he seemed drained and coarsened by a military occupation that has engendered continuous Palestinian struggle and ensuing grief. The man spoke with great yearning for the land of Palestine, but lacked conviction. What more could the Palestinian people do? How could they oppose a military presence and expand in an area where they simply are not allowed?

“We will continue to resist the occupation to have a free Palestinian state.” Through the veil of restlessness and victimhood, the mayor asserted his right to resistance. His dual persona embodies that of the Palestinian people, torn between nationalist desires and the emotional bounds of perpetual conflict. “There is no solution for us than staying here.” Though the end of the conflict is uncertain, the Palestinian people yearn for peace and coexistence within the bounds of one state, assertions made by the Palestinian mayor. Concluding the day with Palestinian representatives after Jewish settlement promoters confused the group, confirming the complexity of the conflict due to varying narratives. Nonetheless, our day in the West Bank was historically and culturally rich, a day of academia in a beautiful setting.