One Day the Sun Will Rise on a Free Palestine

This blog entry is brought to you by Harry Q…

It is a sobering sight to see children playing amongst the ruins of buildings, throwing bottles against walls and into vacated buildings. They come close to us as we walk around the camp, greeting us with cries of “Allahu Akbar!” As we walk in-between crumbling buildings, we see throngs of children in school uniforms walking along, mouths agape when they meet our gaze. For every adult, there are easily 30 kids, whooping and hollering at us in Arabic, drawn primarily to Danya, one of the Arabic speakers on our trip. Our tour guide through the ruins brings us to a mural that I photographed and put below. It is of three martyrs who were born and raised in this very camp. Two were responsible for plane hijackings and the deaths of hundreds of innocents.

Here, they are heroes.

Here is the Dheisheh Refugee Camp, just south of Bethlehem. Many famous terrorists, or freedom fighters, grew up here, descendants of the original refugees who settled in this makeshift town for what they hoped would be a few short years. The name refugee camp is deceiving. The word camp implies a temporary installation, and the Dheisheh camp began as just that, with 800 people in a square kilometer of space. Today, more than 60 years later, there are 13,000 people living in the same area, passing on the story of displacement to future generations. There are no tents, no makeshift shacks, no central water wells or community showers. These are buildings made of concrete, with plumbing and electricity, community centers and schools, shops and restaurants. If it weren’t for the rubble, you would feel as if you in a particularly claustrophobic neighborhood in Bethlehem. If it weren’t for the portraits of martyrs, you would believe that this was just another town in the West Bank.

Our tour guide claimed, “We are not here for humanitarian reasons.” It seems that this town has become a political message to Israel and to Palestinians who are willing to compromise and negotiate: we will take nothing less than all of Palestine. This theme of anti-normalization, of absolute disdain for acquiescence, is one that was reinforced over and over today.

We then journeyed to the tomb of Rachel, an important site in the Old Testament and the supposed burial site of one of the Four Mothers. It was nestled in the separation wall, an assuming entrance into a gleaming cavern fitted with marble and Jerusalem Stone. It is rare that I find myself out of place in Jerusalem; even the sites specific to one particular religion draws people from all over the world, come to gawk at the historical significance of each holy area. However, Rachel’s Tomb was filled with the mutterings of Orthodox Jews bowing to the grave of Rachel, appraising us coolly with uncompromising stares. I often feel out of place in Israel, but here, I felt unwanted, as if I were encroaching.

A short dividing wall that borders the road leading to the Aida Refugee Camp is covered in murals memorializing the Palestinian villages lost in the Nakba. All the buildings in this area of the West Bank are covered in pro-Palestinian independence graffiti. The security fence, which is a proper wall that towers 20 feet into the air, has turned into a message board for dissent. Banksy has an installation there, and his work sits among similarly themed artworks that depict doves with bulletproof vests, mothers crying over dead children, and wreaths of olive branches jockeying for attention with the names of countless martyrs.

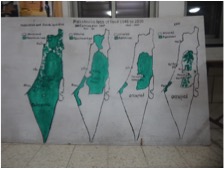

At the Aida Refugee Camp, there is a piece of plywood, 5 feet by 3 feet. It has been painted white, and it depicts the change in territorial control in Palestine/Israel from 1946-2000. What is striking is that Israeli territory and zones of control are not referred to as Israeli, or Jewish, but rather as occupied. Twice today we have been told, “We are not a humanitarian cause.” The word refugee is perhaps the most deceiving of all, for these people are not here with nowhere to go. They stay to make the ultimate political statement: we will not compromise. Generations are bred here with the mantra that Palestine must be, will be retaken, from Gaza to the Golan Heights. There is a general air of revolution, of dissatisfaction with authority. Israel and the IDF are spoken of in the same breath as the Palestinian Authority and the National Security Forces, as people in these “refugee camps” vocalize their doubts that either party is interested in the welfare of Palestinians.

Our final stop of the day was at the Tent of Nations, a Palestinian farm that has existed since the Ottoman Empire. The Tent of Nations has fought since 1967 to hold onto their territory in Zone C, as they are slowly surrounded by settlements and the IDF. Multiple times soldiers have one onto their land and uprooted trees, and they are constantly harassed by settlers. Today has been focused mostly on the Palestinian narrative, and it is hard not to feel biased when the tragedy of the occupation is thrown in your face, but at the Tent of Nations, I felt sick. The people living on this land had the deed to the property, complied as much as possible with the law, went out of their way to not interact with settlements. And yet they were still being persecuted for their mere presence, struggling to survive each year.

This tour has been amazing, giving us the full scope of the conflict, playing devil’s advocate when it is not popular, pressing us to ask our questions and search for solutions to this conflict. Today, I felt hopeless, identifying with the Palestinians in a way I never had before. This conflict is full of hope and horror, pain and beauty. It is human to sympathize with both sides, but today, if it weren’t for the strength of speakers and their causes, their indomitable will to survive and thrive, I would’ve felt useless. Supporting these people in their endeavors is the only way to move forward and end the fighting.